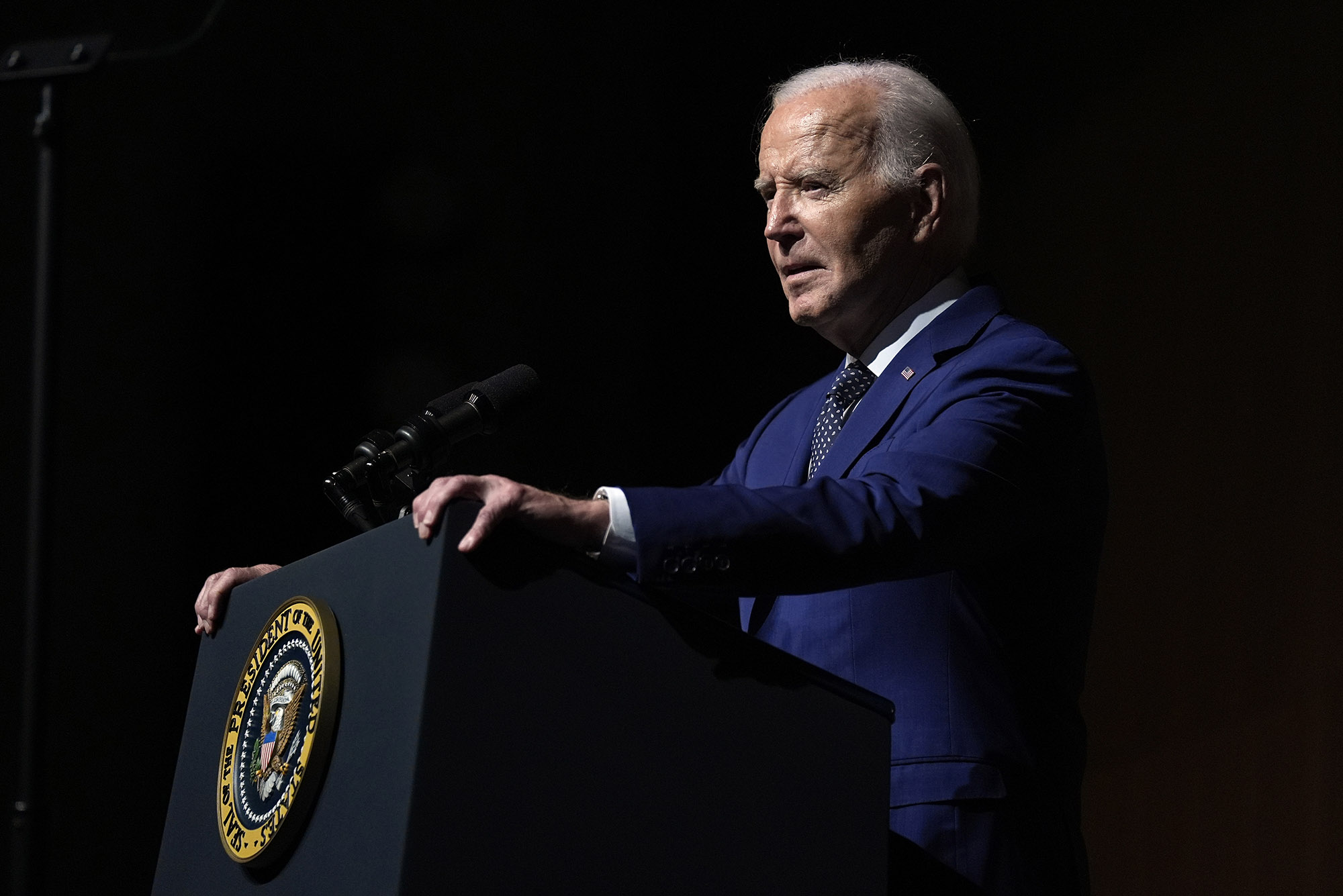

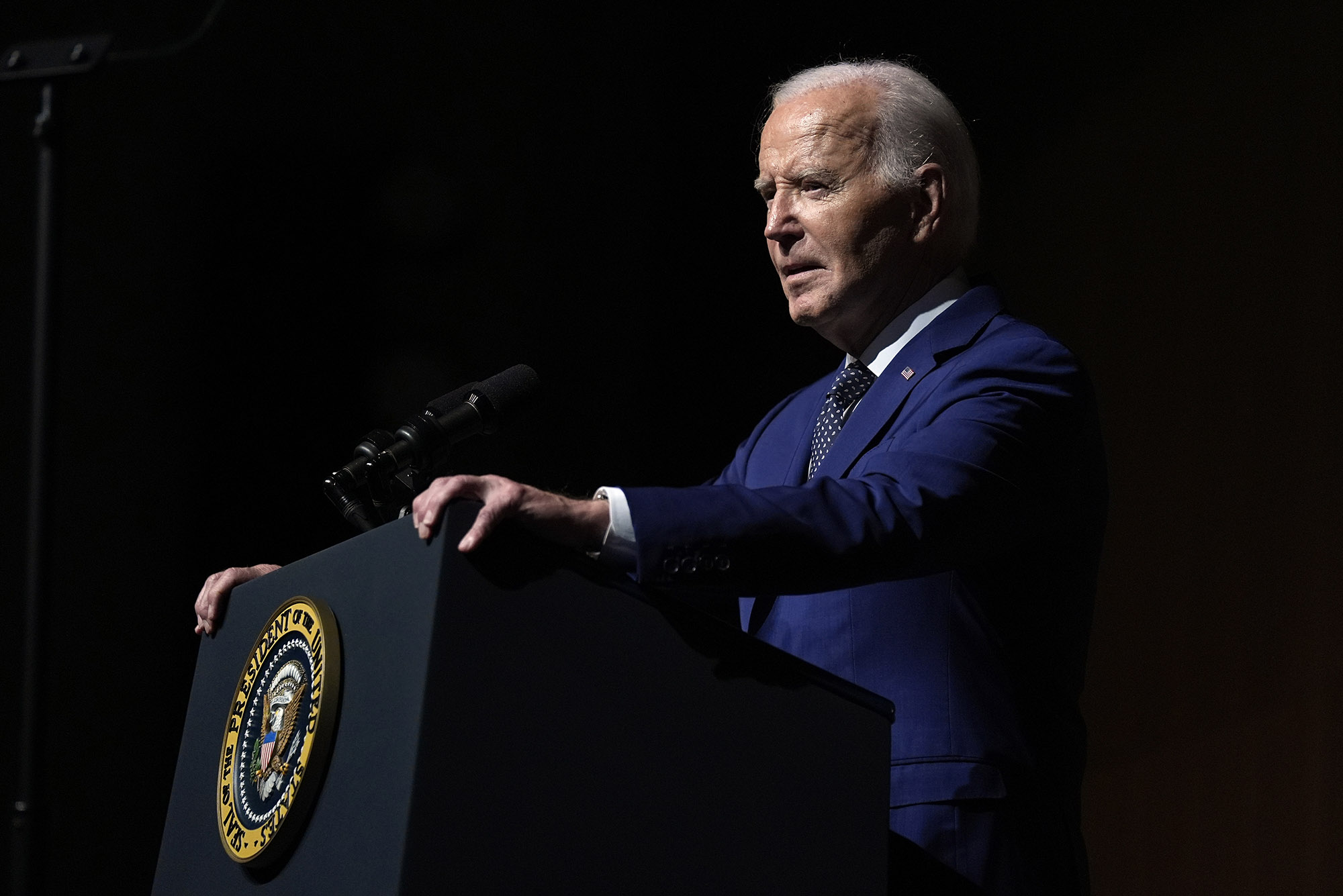

President Joe Biden, speaking at an event commemorating the 60th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act on Monday, July 29, 2024, at the LBJ Presidential Library in Austin, Tex. He took the opportunity to detail his proposals for sweeping Supreme Court reforms, as well. AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta

Warning that the US courts were being weaponized as part of an “extreme” conservative agenda, President Joe Biden on Monday called for two major Supreme Court reforms, and proposed a constitutional amendment that would rein in a president’s immunity—moves that were widely viewed as an effort to button up his 50-year legislative legacy in public office.

Biden spoke Monday at the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum in Austin, Tex., in his first public event since announcing he would not continue his run for another term in office.

Prior to his remarks, the president outlined his reforms to rebalance the courts and rein in presidential immunity in an op-ed for the Washington Post. The Supreme Court has been besieged by scandal in recent years, eroding public trust in the institution. And, in early July, the court drastically expanded the notion of presidential immunity to include almost anything a president does while in office—a move many legal and constitutional scholars viewed as far outside the bounds of legal precedent.

First, Biden called in the op-ed for a constitutional amendment that “would make clear that there is no immunity for crimes a former president committed while in office.”Second, he suggested that there be term limits for Supreme Court justices, recommending that the nine justices be held to 18-year terms, so presidents would nominate a new justice every two years.

Finally, he called for a binding code of ethics for members of the high court; something that would require justices “to disclose gifts, refrain from public political activity and recuse themselves from cases in which they or their spouses have financial or other conflicts of interest.”Vice President Kamala Harris, who has emerged as the likely Democratic presidential nominee since Biden dropped out of the race, said she supports his reforms.

All three of these proposals would need congressional support, and a constitutional amendment requires a two-thirds vote of both houses in Congress and support from three-quarters of the states. Biden’s now lame-duck presidency, coupled with a split Congress and a deeply divided nation, makes the passage of any of these reforms highly unlikely. BU Today spoke with Jed Shugerman, Boston University law professor and Joseph Lipsitt Scholar in the School of Law, about these proposals and what they represent for US politics.

How likely is it that he could pass such an amendment in what is now a lame-duck presidency with a divided Congress?

Shugerman: A zero chance before the election. A constitutional amendment requires two-thirds of each house and three-quarters of the states. If the Democrats win the House and keep the Senate, and if Vice President Harris wins the presidency, there is a small chance of a coalition of Democrats, Republicans who are eager to turn the page from Trumpism, and Republicans eager to keep criminal checks on the next president. But I wouldn’t bet on it.

Shugerman: We have had 234 years without presidential immunity. The change was in July with the decision in Trump v. United States. If Trump wins in November, he can stop the federal prosecutions, and the courts will protect him from the remaining Fulton County prosecution. If he loses, the federal courts will have to navigate the immunity decision, because any amendment will take too long to be ratified. But after that, we will return to the workable status quo ante: no presidential immunity. And that is consistent with the Framers having rejected monarchy and presidential immunity—the historical evidence against presidential immunity is overwhelming, which belies the Roberts Court’s conservatives claiming to be “originalists.”

Shugerman: Biden’s op-ed in the Washington Post and the White House press release did not specify if they supported a constitutional amendment or a statute, which is wise. Many scholars agree that any term limit on Supreme Court justices would require a constitutional amendment, because the Constitution guarantees them tenure “during good Behaviour.” In my research on the history of good behavior, summarized in my thread yesterday, the Framers—both supporters of judicial independence and its critics—thought the meaning of good behavior was obvious: tenure for life, with impeachment for misbehavior as the only limit. Many non-originalist scholars disagree, but no matter who is right, the Supreme Court would strike down any statute imposing term limits—and it could do it immediately, similarly to how it has misused history to strike down more limited “good cause” protections for independent agencies.

It is a good strategy to run against the Roberts Court, but the strategy could backfire if the campaign [for reform] seems to flout the Constitution and the rule of law.

If the term limits are only by statute, the Supreme Court would strike them down immediately, and maybe by a vote of 9-0.

If the term limits are imposed by constitutional amendment, then they would work like six-year terms for Senators, two-year terms for members of the House, and term limits for presidents. At the end of 18 years, the justice is no longer a justice, and the president and Senate could have a new appointee ready to start that same day. Of course, political actors could always refuse to comply with the law, and we have recently seen a loser of a presidential election try to cheat his way past an election and the end of a term. The political system worked well enough in January 2021 to withstand that attack, but a month later, the Senate failed to convict and disqualify, and here we are in 2024. We can’t take it for granted that our national political culture will demand the enforcement of constitutional law and basic democratic norms.

This two-year schedule is the best part of the proposal, but it is imperfect. Supreme Court justices have been timing their retirements for their partisan or ideological commitments: as justices approach retirement age, conservative justices wait for a Republican president, and liberal justices wait for a Democratic president. Conservative justices have been better at this timing.

Justice O’Connor reportedly said on election night 2000, when it appeared Vice President Gore would defeat then-Governor George W. Bush, “Oh no, now I can’t retire.” A month later, she was the fifth vote in Bush v. Gore. She didn’t retire in those four years, probably because of the cloud of Bush v. Gore, but soon after Bush won reelection, she retired. Justice Kennedy similarly retired after he received signals or assurances from the Trump administration. On the other hand, health is unpredictable, and a sudden death during an election year can hyper-politicize a presidential election. See Justices Scalia and Ginsburg.

Eighteen-year term limits mean that every president gets two regular 18-year appointments. However, what if a Senate blocks a president from appointing one or both seats? Then we’re back to 2016, when President Obama nominated Judge Merrick Garland, and Senator McConnell (R-Ky.) and the Senate Republicans kept Scalia’s seat open past through the election. Could an obstructionist Senate block both appointments over four years, so that the next president would have those two open seats plus two more regular appointments?

The better solution is to pass a statute that makes each current justice’s seat their own seat, and that seat expires at their retirement or death. Then every president gets a new appointment every two years. If the president and Senate cannot agree on an appointment in those two years, that opening expires—no reward for obstructionism.

Over the next 20 years, the court would very gradually expand, probably to 12 or 13, as 10 new seats open—but some of them likely go unfilled due to partisan disagreement, and some of the more recently appointed justices remain on the court. This is not “court-packing,” because it is so incremental and equal opportunity for both parties to win presidential elections and take advantage of the regular appointment schedule, two per presidency.

This proposal addresses the real problem, the Supreme Court’s far-right 6-3 personnel, and it does it more immediately, but also moderately and more valid constitutionally than term limits. But the Democrats probably understand that any form of court expansion would be misportrayed or misunderstood, and that political risk in 2024 may be greater than the reward.

We’re not sure what a “binding code of conduct” means. Generally, the lower federal courts and state courts have a process for parties and citizens to file judicial ethics complaints, and the judges enforce those ethics codes on each other. For example, if a trial or lower appellate judge has an alleged conflict of interest or an alleged appearance of bias, but refuses to recuse, then appellate judges can hear the legal complaint and can use “disqualification,” the appellate form of forcing a lower court judge to recuse.

The Supreme Court adopted a more voluntary “code” last winter, but it has no provision for parties or citizens to bring a judicial ethics complaint against them, and there is no disqualification provision. The justices only self-enforce. Over 50 years ago, when President Lyndon Johnson nominated Justice Abe Fortas to be chief, a financial scandal and an appearance of impropriety led to self-enforcement: Fortas withdrew from the nomination and also resigned entirely.

That self-enforcement is unimaginable now, as Justice Thomas’ wife allegedly was involved in a conspiracy to overturn the 2020 election, and both Justices Thomas and Alito face significant questions about receiving massive gifts from billionaires, among other concerns about extreme political symbolic statements.

The better approach is to change the anti-corruption laws to make it a crime for judges to receive significant gifts, without having to prove bribery. Then a justice could be convicted of a crime. This federal law would require a federal prosecutor and a unanimous jury. The law should be explicit that state prosecutors have no jurisdiction to enforce these criminal prohibitions.

Biden Calls for Supreme Court Reforms–But Are There Better Options?